Implicit in the paradigm of Western modernism is the notion that the avant-garde movement is predicated on a radical reversal or insistent deviation from established artistic canon or norms. If one adopts this Western historicist view-one that presupposes some kind of revolutionary breach within the continuum of culture and the current production of art-then an initial encounter with Ukraine’s art of the first three decades of the twentieth century would not seem to justify such a figurative description. Instead, what can be found in the avant-garde of Ukraine is not the destructive nihilism that typifies futurist or dada art, but rather a constructive acceleration of artistic processes and events that would establish a modernist identity for Ukraine bent on reclaiming centuries of art lost to history. Rather than destroy any links to the past and discredit any affiliation with them, what we would want to call a “Ukrainian avant-garde,” therefore, identifies discontinuities between the art of the present and that of the past and elides them into an unexpectedly anomalous and disjunctive new art. References to ancient Scythian horsemen and primitivist Cossack Mamay imagery in the work of David Burliuk points to the kinds of anachronisms that are inherently a part of the Ukrainian avant-garde and highlight its paradoxical features. As tempting as it might be to claim a large degree of borrowing from Western modernism on the part of the Ukrainian artists, what becomes apparent upon closer scrutiny is that what makes this art avant-garde is that it is, in fact, decidedly nonconformist.

The Ukrainian avant-garde arose out of a diacritical relation to the emerging universalizing aesthetic of symbolism, expressionism, and cubism. By mitigating local traditions against the universalizing principles of modernity, the new formalist currency was plainly converted to local referents. If Picasso, in his relief Guitar of 1913, made use of sheet metal and wire, shifting from painting and collage to three-dimensional construction to challenge the illusory nature of painting, then for Volodymyr Tatlin, raw baseboard and decrepit painted wood paralleled Picasso’s experiments. Despite employing the cubist iconography of musical instruments, however Tatlin’s work makes no reference to the guitars, violins, or clarinets of Picasso’s or Braque’s cubist paintings; rather, his Construction in Blue and Yellow bears an uncanny resemblance to the bandura – the native Ukrainian musical instrument that Tatlin had played professionally. Similarly, the minimalist aesthetic that resides in the “constructivist” work of Vasyl Yermylov (who, by contrast, does reference the cubist guitar) is probably more aligned with the pristine geometries of folk tapestries and weavings (interwoven with rich pure color against clear white ground as seen in his book or magazine covers or political posters and commercial advertising) than in the aesthetics of constructivism per se, even though Yermylov’s design elements and intuitive understanding of space as a formal element of relief construction echoes the functionalist aesthetics of the 1920s.

The inclination to suggest that Ukrainian avant-gardism is gratuitously derivative of its Western models, therefore, is to overlook its natural predisposition to reductivism and geometric form-features that constitute and imbue all forms of Ukrainian folk art. For someone like Alexandra Ekster, the language of modernity, and especially the avant-garde’s predilection for paring down observed nature to its essential properties, belies an intimate familiarity with Ukraine’s material culture. The use of schematized forms to express a cosmic worldview is directly associated with abstract motifs utilized in local handicraft and folk customs.

David Burliuk – Cossack Mamay, 1912

Just as Western avant-garde movements were predisposed to incorporate primitivist sources into their formal programs (one need only mention the use of tribal masks in cubism or the ethnological sources and the crude woodcut tradition that surfaces in modern expressionist German art) so for Ekster, the embroidered cross-stitch patternings in vivid colors served the same function as did the simple forms of Iberian artifacts that inspired Picasso. But where the cubists and expressionists sought reductionism in tribal art of other cultures, Ekster and her contemporaries, especially Kazimir Malevich, found them at their doorstep – in village embroideries, textile weavings, and bright peasant costumes. In an enterprising gesture of melding fine and folk art within the climate of art during the interwar years, the abstract geometric work of Ekster and fellow female painters, Maria Vasilieva and Nina Henke, provided modernist templates for embroidered designs on scarves, pillows, and other artistic merchandise created in village-workshops on the outskirts of Kyiv. These handcrafted objects made by peasants at Verbivka were later sold in shops in Poltava, Moscow,

Berlin, as well as Kyiv. The complementariness between the exuberant compositions of Exter and the swirls of vivid color in the naive paintings of Hanna Sobachko-Shostak captures the intense interdependence between these two spheres of art production and points to their compatibility within a modernist context.

Ekster’s Still Life with Easter Egg seems intent on making that point. Like Tatlin who adapts Western experimentation to local culture, Exter substitutes a cubist wine carafe for a pysanka in her painting. In this particular case, it functions perhaps more as a token of identity and a mark of her affiliation with the Slavic culture than a motif of abstraction. However, the abstract devices of the pysanka-which include clearly defined axes, the precise delineation of planes, shapes broken down and “faceted” into smaller bisected units-all find direct resonance in the rigorous orientation of perpendicular and parallel diagonals of Vadym Meller‘s stage costumes and Exter’s stage sets, while the reductive elements of the pysanka-its repetitious webbing and interlacing of flat patterns, the play with positive and negative space, and an alternation of dynamic rhythms-finds its way into the egg-shaped contours and chiasmic compositional structures of Exter’s non-figurative works. Furthermore, the pysanka’s emphasis on geometric forms as structural modules resonates with the spatial constructivism of Oleksandr Khvostenko-Khvostov‘s stage designs and supports the consistency of spirited obliques in the compositions of Anatol Petrytsky and the animistic portraits of his contemporaries which, in their presentation, also evoke the magical realism of Otto Dix and Germany’s Die Neue Sachlichkeit. On the other hand, Petrytsky, like Burliuk, also draws on the exuberance of the Kozak Baroque style, with its sweeps of color across swaths of contoured form. The attention given to surface texture and a general spirit of unrestrained monumentality add a psychological dimension to the work that is inflected by the legacy of long standing traditions through which the political tensions of the late 1920s came to be expressed.

In one of the earliest attempts to theorize upon the formalist aesthetics bound up with the “new” geometric art, Alexis Gritchenko, proposed that the current interest in French art among Russian and Ukrainian artists, had nothing to do with a desire to copy or imitate cubism; rather, it was the expression of a genuine “national” quality that was rooted in ancient iconography inherited from Byzantium.

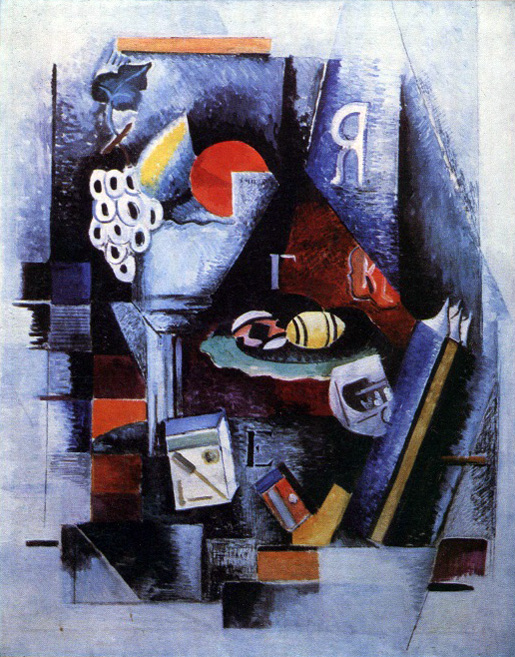

Alexandra Exter – Still Life with Easter Egg, 1914

As exemplified in the sculpture of Olexandr Archipenko, who always shunned the cubist label, the use of angles within a controlled flattening of space and the subtlety of an inherent dynamic movement (or animus) within the work comes to the modern Ukrainian artist by more traditional routes. By bridging the chronological ruptures that had separated modern Ukraine from its antecedent sources, these artists have succeeded in blurring the margins between the art of the present and that of the past, while, as seen in the art of Burliuk, Exter and Yermylov, they also successfully meshed the traditionally separate fields of folk and fine art.

When independence for Ukraine took to the streets in the wake of revolutionary events during 1918 and 1919, the blurring of borders between “high” and “low” arts found full expression in a convulsive paroxysm of color on the streets of Kyiv. In a zealous expression of belief in the promise of a new and brighter future, artists decorated the city with festive banners, rendering a bacchanalia of bright hues that portended vibrant socio-political changes. Klyment Redko described the sight in 1919 as “Bach fugues that reflect the harmony of the cosmos, Matisse, the simplicity of Assyrian and Egyptian statues, the gold of Byzantium and St. Sophia, Cezanne, Titian – and here, a child’s drawing, a colorful lubok, the colored masks of folk theatre!” Most of the contingent of artists who had been exploring new forms for at least a decade took part in dressing up the city during those jubilant days. They had been prepared by a decade of avant-garde activity that boldly reformulated the conventions of art to redefined art’s function as a form of collective expression.

What came to be recognized as the artistic avant-garde in Ukraine was inaugurated with a series of historic Kyiv exhibitions: the Lanka (Link) in 1908, the two “International Salons” (organized first in Odesa by Volodymyr Izdebky in 1909 and 1911 respectively) , and the Kiltse (Ring) of 1914, which showcased the work of Olexandr Bogomazov. The first of these, Lanka, was organized by the enterprising David Burliuk, who together with Ekster, featured 26 painters, many of them newcomers to the “avant-garde” circuit, and some of them, such as Kharkiv artist, teacher, and activist, Evgeny Agafonov, chosen perhaps not for his artistic innovation, but because of his efforts to stimulate interest in modernist art in Kharkiv. The most unlikely participant in the exhibition was Evhenia Prybylska whose abstract motifs – derived from Ukrainian folk embroideries and weavings – contrasted sharply with the “urban” futurism of upcoming avant-gardist, Bogomazov. The inclusion of such diverse artists in the Lanka exhibit typified what in hindsight can be claimed as the Ukrainian avant-garde’s most typical feature – it’s generally inchoate character and its resistance to any strict classification.

Lanka was avant-garde, therefore, not because of the quality of its artist-participants, but rather for the boldness of the enterprise. Not only did the exhibit brazenly accommodate a broad range of stylistic approaches, but did so with demonstrative bravado, scandalously launching a new chapter in the history of Ukrainian art. At the opening of the show, Burliuk issued his first public utterance on the emerging state of “new” art. Brashly titled, “The Voice of an Impressionist in Defense of Painting,” Burliuk’s boisterous pronouncement was directed at vernacular tastes. By employing vulgar references to bacon lard – a peasant staple (as well as a popular Ukrainian culinary delight), he exalted the “enlightening” powers of “pure art” which, unfortunately, “the crowds cannot see” because “the fire of this art does not burn, and [unlike] the odor of [burning] lard cannot be smelled.” Seeing the New Art not as an aesthetic novelty, Burliuk described it, metaphorically, as “a flaming column, carrying the soul into a blue purgatory.”

Olexandr Bogomazov – Portrait Of a Woman, 1915

The symbolist overtones of this statement below Burliuk’s affinity for the dissolution of “literariness” in painting and, instead, underscores the importance of freedom and license to explore all avenues of art, an unbounded spirit of artistic production that would transcend the rigid imitation and illusionistic realism that, to their way of thinking, brought about a decline in Western art. As Gritchenko identified this crisis in Western art, so too did Burliuk blame academic realism that, through its emphasis on the narrative, had been responsible for ossifying the medium of painting, extinguishing its expressive potential. The exhibition Lanka put into motion a lively course of experimentation and inventiveness that would sustain an avant-garde spirit for two long decades in Ukraine; yet the International Salons that followed in 1909-10 and 1911-12 instantiated what was to become the pluralistic and idiosyncratic character of the Ukrainian avant-garde.

Beginning in the winter of 1909, Odesa sculptor Volodymyr Izdebsky ventured on exposing to audiences current trends in modern art, by risking an aesthetically “uneven” exhibition in which the works of leading Paris masters were shown in conjunction with still largely unformulated directions developing locally. Since Izdebsky and David Burliuk had been friends since their student days (first in Munich, then in Odesa), some of the “local” participants had been represented previously in exhibitions organized by Burliuk in Moscow, Kherson, as well as at the Kyiv Lanka. Their work must have seemed “beside the point” compared to the recognized French modernists. Notwithstanding this eccentricity (or maybe because of it) the unprecedented nature of the enterprise and its scope of commitment to a New Art amounted to a bold avant-garde gambit. When first opened in Odesa, the transgressive nature of the Salon was conceived as a totalizing event that would awaken and affect every field of cultural activity throughout the city. Izdebsky issued a veritable challenge pitched at the art establishment. In a defiant gesture to change its course, this unusual public display and its accompanying events were thus bound to stir controversy.

In organizing his “Salon” Izdebsky had snubbed his teacher Kiriak Kostandi, a reputable senior artist who had formidable influence over the realist painters of southern Ukraine. Izdebsky’s mentor, conspicuously branded as an artistic anachronism, had become the public scapegoat for demonstrating the new aesthetic turn. Kostandi’s impassioned opposition to the first “Salon” unwittingly brought even more attention to this momentous occasion. His high visibility and respected stature in Odesa art circles elicited vociferous support for the status quo, fueling a press campaign of derision against the “charlatanism”, “ignorance”, and “indecipherability” of art shown in the Salon. Sharp criticisms launched a vehement polemic that filled the pages of the local newspaper, Odesskie novosti [Odesa News], A particular work by Volodymyr Burliuk – a painting entitled “Paradise”, – became the “sacrificial” token of an emotional debate stimulated by the generally negative appraisal of the first of Izdebsky’s Salons. One reviewer mockingly asked: “What is the meaning of this work? Neither a torso without legs and a head, nor a vase for a cactus. Why is the woman kissing a donkey, or is it a toy dog?”

Ironically, the segmental patterning of V. Burliuk’s painting-typifying his current exploratory “stained-glass” style of broken and compartmentalized abstract units-paralleled a similar overall flattening of form and mosaic like contouring that his compatriot, Mykhailo Boychuk was developing concurrently as his hallmark “neo-byzantine” style back in Paris. Yet Burliuk’s pastel color choices made clear that his orientation emanated not from the inspiration of medieval art, but as an attack on the illusionism of naturalistic landscapes and figural painting practiced by the Society of South Rus’ Artists (TYuRKh) which Kostandi had headed for years. Local Odesa painter of realist genre and landscape scenes, Petro Nilus – another member of TYuRKh-in a critical review of the Salon identified, albeit not without sarcasm, two directions emerging out of the Salon: “one group paints only that which does not exist in nature; the majority of others paint was is in nature, but from the standpoint of the naive experience of the child. Neither group shows any talent!”

What Nilus failed to understand was that a new era had been ushered in by the abstraction of symbolism, and that Burliuk’s segmentation and cropping of his forms-derived from the decorativism of symbolist art-finally separated the new art from the constraints of academism and detached pictorial imaging from stale mimetic representation and naturalistic verisimilitude. When the Salon was reprised in Kyiv in February of 1910, more satire filled the popular press, but this time critics were also willing to accept the Salon’s “nonpartisan” features and accept its “laboratory” premises, acknowledging – even if somewhat reluctantly – the importance of the aesthetic shift that they ultimately recognized had taken place. This proved to be a victory for the avant-gardists, who extended a tour of the Salon into Kyiv, St. Petersburg, and Riga. When the second “international” Salon was scheduled to take place in Odesa in December 1910, the French masters were no longer represented; instead, the strength of the Munich school was intensified by fifty-four recent paintings by Vasily Kandinsky, and new local artists, such as Tatlin. Financial difficulties curtailed plans for a similar itinerary for the second “international” Salon, which, after opening in Odesa, would continue only in Mykolaiv and Kherson.

Volodymyr Tatlin – Counter-Relief, 1917

Izdebsky’s Salons served to legitimize the translation of diverse local impulses into urbane, modernist terms. In this mission, it created an artistic network of unlikely sites of a burgeoning avant-garde; their regionalism and geographic distance from the modernist ethos of Europe was not a handicap, however; if anything, it was regarded as an asset. The Salons succeeded in expanding the influence of modernism latitudinally across the European continent, while also maintaining a corridor of influence that extended from southern Ukraine, through Kyiv, past Russia, and into the Baltics. All in all, the sheer volume of works shown in the two Salons was stunning in and of itself, and was bound to alter future artistic practices. Izdebsky presented the opportunity to survey the chronological development of early twentieth century modernism-beginning with the French Nabis and Fauves through to Giacomo Balla – the sole representative of Italian Futurism. The third important exhibition of Ukrainian avant-gardism, “Koltso”, was a fitting climax to the work accomplished by the Salons for it exemplified the new spirit by showcasing the achievements of Olexandr Bogomazov.

“Koltso” [“Kiltse” (Ukr.) or “Ring”] arose out of a most unusual relationship forged between the students at the Kyiv Polytechnical Institute and a few of the most progressive visual artists of Kyiv. Chemist (and artist) Mykhail Denisov organized, in conjunction with Institute’s circle “Art”, an exhibition that went relatively unnoticed amidst the flurry of art exhibits, concerts and Futurist programs that energized Kyiv in the early months of 1914. Yet this was the event that was to define the most prominent aspect in the evolution of “New Art” in Ukraine – its teaching mission. Alexandra Ekster’s growing reputation in Kyiv art circles, and her participation in this exhibit gave visibility to the show; the works of Vasilieva, with her cubist and orphist canvases, relying fully on the color aesthetics of folk art, must have made a strong visual impact on the spectators. But the exhibition was noteworthy for one primary reason: it brought to public attention the principles of abstraction that are fundamental to modernist art and exposed Bogomazov not only as an artist of singular talents, but as a thinker on a par with other great masters of his time – Kandinsky and Malevich.

A “credo”- not of a group, but of a commitment to a new orientation about New Art-was published as the preface to the catalogue of the show. It announced the “liberation of painterly elements” from the shackles of narrative pictorialism – the servitude of academic painting. Under the generic rubric of the committee as signatory (although, no doubt, it was Bogomazov who wrote it, for it reflects his larger principles verbatim), the statement advanced a new aesthetic based on the examined relation of four basic elements of painting: line, form, pictorial surface, and color. Through the principles of the four elements, Bogomazov developed his “system” of painterly analysis in a profusive treatise during the winter of 1913-14. Like Kandinsky’s “On the Spiritual in Art” of 1912, so Bogomazov’s “Painting and Elements” can be counted as one of the key theoretical formulations of early twentieth art. Never published in the artist’s lifetime, his ideas would only find realization in Bogomazov’s life as a dedicated teacher-first in a school for deaf mutes, then in a school for children in the Caucasus, and finally, from 1922 to 1930, as faculty at the Kyiv Institute of Art.

Bogomazov’s theories formulated in didactic terms what Izdebsky’s enterprise had made available to the public eye: a new “synthesis” of art and modern life, seizing the simultaneities of organic, harmonic impulses that define the urban context of futurism. “The face of future mankind is the city”, Izdebsky wrote in his essay, “Griadushchyi gorod” [The Coming (Anticipated) City].19 In the years 1913 to 1915, when Bogomazov made numerous drawings of Kyiv city streets seen sloping and plunging dynamically across the picture plane, the typography of the city catalyzed the artist’s study of the “painterly” function of line within an artwork. Parallel to the theoretical formulations of Kandinsky, Bogomazov regarded line as the instigator of motion, direction, and concentrated energies. He describes the variable qualities of these energies by focusing on the representation of a simple table: “The feature of a line is movement – gravity, lightness, quickness, slowness, softness, dryness, etc. Hence, depicting only a natural table but not transmitting the rhythmic fluctuation, line loses its painterly sense; the lines of that very table, associated with a specific rhythm, are full of meaning”. Imbued with futurist notions about force lines and the penetration and syntheses of environmental energies, the elements of line and color, became the primary agents for transmitting these forces in Bogomazov’s art.

Bolstered by the effect of the Izdebsky’s Salons, futurism’s march on the “provinces” was concentrated on a string of towns across Crimea, Central and Eastern Ukraine, and the region of the Caucauses, which became the domain of the Hylaean Cubo-futurists headed by David Burliuk. These regions were assailed with public lectures, declamations, and performances staged by Burliuk and his cohorts, Vladimir Mayakovsky and V. Kamensky. Alexei Kruchenykh, who hailed from Ukraine as did Burliuk, created futurist poetry that was inspired by the vernacular turns of Ukrainian phrases, its dialects and local expressions, making futurist behavior seem at once both alienating in its brazenness, yet oddly familiar. The aggressive display of “artistic psychopaths” astonished the audiences who were brought into direct contact with them. The confrontation transformed the main cities into arenas of unexpected artistic experimentation, introducing new faces into the constellation of Ukrainian avant-garde art. In Kharkiv, Maria Sinyakova – friend of the Hylaean futurists-serves as a prime example of the universalist blending of the indigenously primitivist and urbane aspects of this movement. Her vibrant paintings, awash with the azure Mediterranean blues recognized in Matisse’s Fauvist canvases, incorporate “eastern” imagery inspired by Oriental kilims, Asiatic tiles and Persian miniatures, as well as the framing devices of menologion icons. The liberated spirit of Matisse’s “joie-de-vivre” comes across as a tapestry of carnal images, contrasting debauchery and virginal innocence in watercolors and gouache paintings.

The mixing of East and West, Russian and Ukrainian, Kruchenykh’s “Ukrainianisms”, and the orientalizing features of Maria Sinyakova’s works define an “otherness” about the Hylaean avant-garde that differed dramatically from the Latinate sources of the Ukrainian Baroque that emerged in the Kyiv-based, strictly Ukrainian (and, for the most part, literary) futurism of Mykhailo Semenko. In 1914, Semenko and two artists (Vasyl Semenko and Pavlo Kovzhun) formed the Futurist group “Kvero” (derived from quaero, the Latin “I search” or “I seek”) which insisted on individualistic will to overturn the values of the past and devalue that which was held sacrosanct and immutable, such as the reverence for the national bard Taras Shevchenko (1814-1861). In advance of the spirit of dadaist Zurich, the nihilism with which Kyivan “Kvero” attacked the status quo was, at least on the surface of things, a parallel replique to Burliuk’s 1912 agitational slogan to “slap the face of public taste”. Semenko’s manifesto “Alone” [Sam] disclosed a bravado that belies a close reformulation of Nietzsche’s exhortations to “cast down God” (or, at least, the “demigods” of art, who, like Shevchenko, were revered and mythologized, especially in 1914-the year of Shevchenko’s centenary celebrations throughout Ukraine). In usurping the title of Shevchenko’s classic collection of inspired poems, the “Kobzar” of (1840) as the title of his own collected futurist verses which Semenko published in 1924 (with several subsequent compilations, again using the same title), the futurist Semenko fulfilled the audacious debunking of figures of culture as promised in his first manifesto a decade prior. Semenko carried this idea well into the 1920s, developing a universalist “Panfuturist” will to power in which he “groomed” himself as the primary instigator. In his dadaist poezo-painting “Parykmakher” [Barber], Semenko makes clear that it is time to pitch the great masters of the Renaissance into the dustbin of past ages.

THE QUATTROCENTISTI

great specialists were

The ITALIANS have died out

Oil is cracking

then

DUST

Pfff

and nothing remains

Mikhail Semenko SHAVED his beard Leonar do/da Vinci.

Kazimir Malevich – Self-Portrait, 1933

From symbolism to futurism, from cubism to constructivism, from Baroque through folk art, the Ukrainian avant-garde constitutes a most unwieldy and unclassifiable phenomenon. It can be found in the secessionist-inspired work of Vsevolod Maksymovych, whose insular bohemian life in Poltava allowed him to indulge in a personal aesthetic of allegory and decadent imagery reminiscent of the dandified realm of the Petersburgian “World of Art” or the fin-de-siecle imagery of Munch; or, at the other end of the spectrum, one can find the diaphanous painting of Viktor Palmov, closest colleague to David Burliuk with whom he journeyed from Kyiv to Vladivostok and on to Japan, championing the cause of futurism. Together they concentrated on crude, everyday scenes of simple folk at work or at leisure; they also shared the theme of the horse-in Palmov’s case, not a reference to Kozak ancestry but a mystifying “spectral” expression of a free and untamed spirit, whose brute liberating force man would do well to capture. In contrast to the tactility “faktura”) of David Burliuk’s paintings which would be built up of impasto mixed with sand and soil, Palmov’s works leave behind all reference to physical materiality as if in a guest for a transcendent experience.

In a similar search for universal wholeness, sublimated in life’s cycles and stages and the legacy inherited from past generations, Fedir Krychevsky‘s triptych entitled Life combines Klimtian ornamentation with a bold sculpting of form which magnify the device of white highlights used in Byzantine iconography. Painted in 1927, Krychevsky’s work signals the “institutionalizing” of the avant-garde in the newly formed Ukrainian Academy. Founded in 1918, the Academy (later renamed the Kyiv Art Institute) was as diverse in background and stylistic development as it was united in its commitment to modern art. The president of the recently-declared sovereign republic of Ukraine, Mykhailo Hrushevsky, a historian by training, appointed artists who believed in the power of art to transform society and move it to its next stage. Hrushevsky’s tactic was visionary: to bring together very strong, confident and highly individualistic artistic personalities, each of whom staked their profession on the discovery and use of a new artistic language that responded to the new era of cultural recovery. Under the “Ukrainization” program of the 1920s organized by the Minister of Education, Mykola Skrypnyk, artists participated as key players in infusing modernism in the experience of a national culture within a new era of independence and cultural self-determination. Those artists, who were once branded as renegades because of their radical approach to art in the years leading up to the revolution, would now build on the merits of avant-garde art to shape a modern Ukrainian visual culture. In keeping with the characteristically broad-ranging interests of the avant-garde, the teaching body at the Academy did not profess any single aesthetic platform. As if to formalize this diversity, students were to select two professors under whose mutual direction they were to undergo their training program. A simple roster of the professorial staff makes clear how varied was the range of stylistic possibilities in the heyday of the institution’s activities. It included: O. Bogomazov, M. Boychuk, V. Krychevsky, A Manievich, H. Narbut, and M. Zhuk, as well as Kazimir Malevich and Volodymyr Tatlin. Oleksa Novakivsky headed up a separate center of artistic training in western Ukraine. His school explored the principles of expressionism and prepared many a student for further training in the academies of Western Europe.

As a non-paradigmatic avant-garde, the dynamic of Ukrainian art of the 191Os to 1930s set up an alternative paradigm of avant-garde activity that was staked on a very different set of norms that cannot not be measured against Western art. What characterizes the Ukrainian avant-garde therefore is that, like other incohesive and seemingly minor avant-gardes of Eastern and Central Europe, it not only “bridged” the formal hallmarks of the historical avant-gardes of Germany, France and Italy, but also postured itself as neither denying nor completely appropriating the discourse that defined the trajectory of mainstream modernism. Instead, by vesting itself in the vigor of longstanding and unique cultural values, as an artistic vanguard it managed to revitalize the very principles that have defined Ukrainian visual culture for many a century. Its rediscovery in the 21st century is timely, given that a new era has once again surfaced in Ukraine.