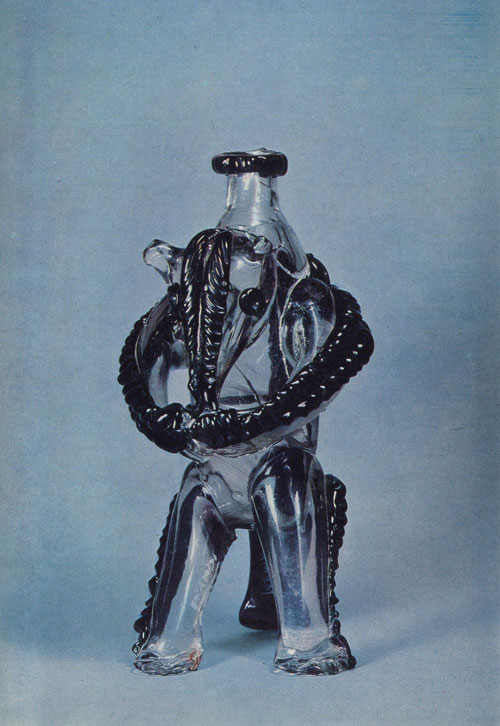

Since ancient times the Ukraine has been renowned for its master glassmen, and their wares have been used by all sections of the population. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, large glass tubs, bowls and dishes were widely used amongst the peasantry for household purposes, and variously shaped carafes, stofs (square bottles), jugs, bowls, and baryla (kegs), were used for liquids. No less diverse were the drinking vessels, goblets, cups, small wine or vodka glasses, mugs and tankards. The particularly popular figured vessels shaped as figures of the bear (symbol of conjugal happiness) or ram (symbol of wealth), were regarded as an indispensable attribute of festive table. The wares were decorated with applied pincered bands, cords, or trailed threading, following old traditions faithfully preserved in glass making since the times of Kievan Rus. One also encounters painted decoration in enamels or in oils, whose design has much in common with Ukrainian mural painting.

These various wares were prepared in small glass shops, hutas, in the woodland areas of northern and north-western Ukraine. The largest number, approximately 120, were in the Chernigov region.

The eighteenth century was a golden age for the art of huta glass. Every object executed and decorated by a master in the technique of free blowing has a live plastic form. The surviving examples are evidence of the fact that the Ukrainian glass-blowers were not only masters of this complicated technique, but also talented designers.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, with the appearance of glass factories, the huta shops, unable to rival them, gradually began to disappear, and the glassmen went to work in glass industry. But in their spare time they still continued to make small objects in the techniques of huta glass. The secrets of the craft were not lost but handed down from generation to generation. There were families where the profession of glass-blower was hereditary, and the traditional forms and methods of huta glass were preserved. This provided a basis for a revival, and a new blossoming, of these techniques in Soviet times.

Bottle in the form of a bear. 18th century. Clear and coloured glass, free-blown, with pincered applied decorations. Height 24 cm.

At present, in Lviv, Stryj and Kyiv there are brilliant craftsmen at work whose whole activity is directed towards resurrecting the beautiful and once-forgotten folk art of blown glass. They are developing the artistic potentialities of the technique of free blowing, using the plasticity, and revealing the beauty, of glass as a medium.

The first objects in blown glass appeared in 1948 at an exhibition of Ukrainian folk art, and were the work of Piotr Semenenko. A descendant of glass blowers, he made traditional vessels — bear-jugs, vases, and decanters.

Recently, the work of the talented folk craftsman Mechislav Pavlovsky has occupied a prominent place in the development of artistic glass. He also comes of a family of glassblowers: in the nineteenth century, three generations of the Pavlovsky family worked in glass factories. The experience of many generations is evident in Pavlovsky’s work. In creating new forms, he starts out from the national folk types of vessels in everyday household use, and attempts to adorn them as imaginatively as possible. In traditional figured vessels shaped as figures of animals, birds, or as human figures, one can always perceive the great powers of observation of the master craftsman, in spite of the conventional form.

Pavlovsky has many students and followers who work with him in the huta glass shop at the Lviv factory of ceramic sculpture. Maryan Tarnavsky, Bogdan Valko, Piotr Dumich, and others, all possess a strong artistic individuality. In the course of long and serious experimentation and persistent work at the furnace, each of them has developed his own manner of vision, a high technical mastery and great freedom in the handling of heated glass in a vast range of techniques.

Their activities have been most fruitful. Along with the traditional wares, there have appeared objects in a variety of new shapes, dessert bowls, vases and objects of a purely decorative nature. These are executed in clear glass, in glass of muted, light water-colour tones, or in bright, intensive colours. The methods of ornamenting them have also been enriched. Thus, in creating sculpture, the artists use, with equal mastery, such techniques as free blowing, applied decoration, and modelling heated rods of coloured glass over a gas burner with the help of different tools.

Stof. 1796. Coloured glass, free-blown, painted in oils. Height 28,5 cm.

The traditions of old Ukrainian huta glass have also acquired a place of importance in the work of professional artists on the staff of the glass factories. Their productions successfully combine the national forms, colouring and techniques with a modern aesthetic vision.

In the works of Lydia Mitiayeva, Evgeniya Meri, Vladimir Genshke, Albert Balabin and others, one can distinctly trace the features common to the Ukrainian national school, in spite of their different artistic methods.

In the Museum of Ukrainian Decorative Folk Art in Kyiv, there is a large collection of old huta glass of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and also of works by contemporary folk masters and professional artists. The extremely interesting and typical works included in this set of photographs give one an introduction to a brilliant and deeply original form of Ukrainian applied art.